Odin is a Labrador retriever/border collie mix. By watching his wagging tail and alert expression, Colorado State University researcher Dr. Glen Golden can sense he is eager to begin his training.

Odin is one of five dogs recently adopted from shelters and animal rescue centers to become detector dogs for wildlife disease surveillance. The dogs are housed and trained at the USDA-APHIS National Wildlife Research Center (NWRC) in Fort Collins, Colorado. They are part of a collaborative 12-month program to evaluate the effectiveness of training and using dogs to detect and identify waterfowl feces or carcasses infected with avian influenza (AI). If successful, this collaboration may be extended an additional 12 months.

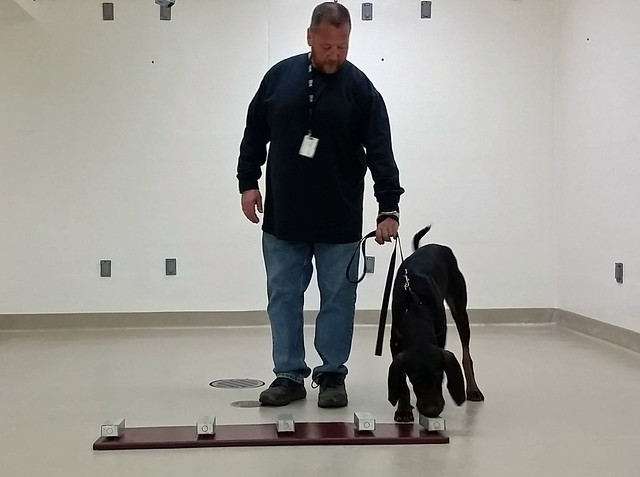

“We train the dogs using positive reinforcement with rewards of food or toys depending on each dog’s motivational preference,” states Golden. “The dogs are trained to respond to specific odors by either scratching at odor boxes containing materials from AI-infected birds or sitting at boxes containing materials from non-infected birds. The dogs cannot touch the infected feces or carcasses, but are able to smell items that are placed in specially-designed odor boxes and vials.”

Previous NWRC and university research shows that some diseases cause odor changes in infected animals. Because their sense of smell is so acute, dogs can detect those changes.

“Dogs have been used for scat, carcass and pest detection in wildlife damage management for many years,” states NWRC research chemist and study collaborator Dr. Bruce Kimball. “They’ve also helped to diagnose diseases, such as lung and breast cancer, in people. Eventually, we hope to train these dogs to successfully detect AI-infected birds or their feces in natural settings and serve as biosensors for this and other costly agricultural diseases.”

Avian influenza, and in particular the highly pathogenic version of avian influenza, is a disease that can be carried by wild birds like ducks without them appearing sick. However, the disease is very deadly to domestic poultry, like chickens and turkeys. APHIS already conducts surveillance testing of hunter-harvested ducks to determine if HPAI is present in the wild bird population as an early warning for the country’s poultry industry. The detector dogs would provide APHIS with another tool to broaden surveillance.

The spread of highly pathogenic AI in commercial poultry and backyard flocks in the spring of 2015 resulted in more than $800 million in damage and control costs, as well as the lethal removal of nearly 50 million domestic birds.

Dogs are not susceptible to avian influenza, but Odin and his colleagues are vaccinated for rabies and other canine diseases they may be inadvertently exposed to while conducting surveillance in the field. Once finished with their training, the dogs will be paired with an APHIS Wildlife Services field specialist for disease surveillance activities or, if found unsuited for surveillance work, placed in an adoptive home.

APHIS has a long history of working with detector dogs to aid in invasive species detection and management— from finding insect pests in shipping cargo to sniffing out brown treesnakes, feral swine, and nutria. View these links to learn more:

- USDA Unleashes Detector Dogs to Stop Feral Swine (YouTube)

- New K-9 Initiative Could Transform Pest Surveys

- A Dogged Last Defense Against Brown Treesnakes

- APHIS Nutria Detection Dogs (Flickr)

NWRC is the research arm of APHIS’ Wildlife Services program. Its mission is to use scientific expertise to help reduce human-wildlife conflicts related to agriculture, natural resources, property, and human and health and safety. For more information, please visit our National Wildlife Research Center website.