This post is part of the Science Tuesday feature series on the USDA blog. Check back each week as we showcase stories and news from USDA’s rich science and research portfolio.

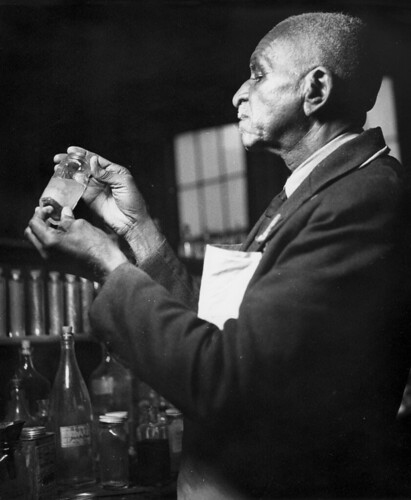

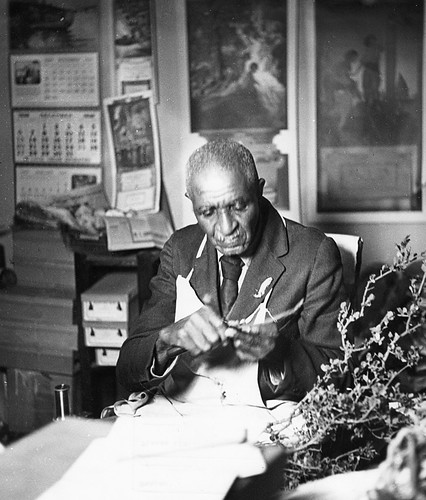

Steeped in African tradition, the practice of storytelling in African-American culture provides a communal sense of pride and reflection, and ensures that history is preserved from generation to generation. African-American History Month honors the work and contributions of African-Americans, including educators, inventors, and scientists—all titles which George Washington Carver possessed. And like the continuity of storytelling, the legacy of Carver’s pioneering research left an undeniable impact on the face of American agriculture.

Born a slave on a Missouri farm in 1865, Carver became the first black student and the first black faculty member at what is now Iowa State University. The well-respected botanist led the bacterial laboratory work in the Systematic Botany Department. But at the urging of Booker T. Washington, Carver moved to Tuskegee Institute in Alabama to serve as the school’s director of agriculture. He used his agricultural research to help black farmers become more self-sufficient and less reliant on cotton, the major cash crop of the South.

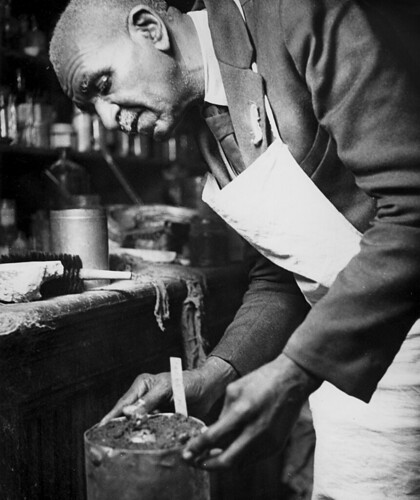

When the boll weevil threatened to eliminate cotton in 1914, Carver developed numerous products and processes that expanded the range of Southern agriculture. At Tuskegee, Carver developed his crop rotation method, which alternated nitrate-producing legumes such as peanuts and corn with cotton, which depletes the soil of its nutrients. His innovations have been credited with the South’s economic survival in the early part of the 20th century.

During World War I, there were shortages of crops and food and Carver began developing alternative uses for sweet potatoes, soybeans, and yes—peanuts. From the peanut--primarily used at that time to feed livestock--he developed hundreds of products, including plastics, synthetic rubber, and paper. From soybeans, Carver invented a process for producing paints and stains, for which three separate patents were issued. Among Carver’s many synthetic discoveries: adhesives, axle grease, bleach, chili sauce, creosote, dyes, flour, instant coffee, shoe polish, shaving cream, vanishing cream, wood stains and fillers, insulating board, linoleum, meat tenderizer, metal polish, milk flakes, soil conditioner and Worcestershire sauce. In all, he developed 300 products from peanuts and 118 from sweet potatoes, in addition to new products from waste materials including recycled oil, and paints and stains from clay.

Along with his duties at Tuskegee, Carver was appointed a collaborator at USDA’s Division of Plant Mycology and Disease Survey of the Bureau of Plant Industry. Refusing several high-salaried job offers, Carver remained on the Tuskegee faculty until his death in 1943, working for $125 per month. When he died, his entire savings of $30,000 was bequeathed to Tuskegee Institute for the study of soil fertility and continued creation of useful products from waste materials.

Agricultural Research Service Administrator Dr. Chavonda Jacobs-Young continues the tradition of storytelling, celebrating the past achievements of Carver with tomorrow’s leaders in American agriculture. This Friday, Jacobs-Young will deliver the keynote address at the Carver Convocation at Tuskegee University.