Our curiosity was palpable in our expressions, we visitors to this South Dakota field, as we pondered the patterns produced by the tops of rocks pressed into grass and soil, patterns tantalizingly organized and purposeful: shapes of things that have been. What stories were held in this small corner of the Black Hills National Forest?

As members of the Forest Service’s sacred sites executive and core teams, our task is to develop ways to fulfill the recommendations from the Report to the Secretary of Agriculture: USDA Policy and Procedures Review and Recommendations: Indian Sacred Sites.

Visiting this sacred place was the starting point of our learning and working together as a team. We needed to experience firsthand the feeling and meaning of this place to help us incorporate an appropriate attitude as we started three days of meetings on how to best implement the recommendations, to better protect and provide access to Indian sacred sites.

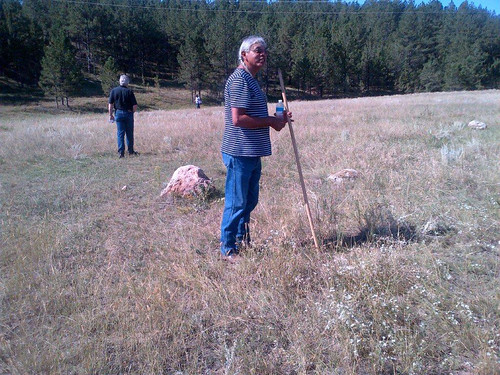

We were guided and educated, at least as much as can be done in just one morning’s time, by Arvol Looking Horse and Tim Mentz Sr. Many years ago, when he was only 12, Looking Horse had been given the enormous responsibility of being the 19th generation Keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Pipe. He is a spiritual leader for the Lakota Dakota Na-kota Oyate, the great Sioux Nation. Mentz is a cultural resource expert with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. He was their first Tribal historic preservation officer and continues to be an amazing source of information about cultural sites for his Tribe.

We learned from tribal elders and Forest Service staff that these stone formations had been misinterpreted several years ago by an archaeologist as teepee rings, or circles of rocks left after having served their purpose of holding down the edges of teepees. The archaeologist had deemed these features as “insignificant” in terms of historical value.

The tribal elders explained that these were no teepee rings. Rather, the stone features were ceremonial shapes, purposefully placed and each with its own sacred reason. Having worked as an archaeologist for some 20 years myself, including having mapped and excavated teepee rings in Montana and Wyoming, I was also aware that these forms were far from the evenly rounded rings I’d seen many times before. They were shapes, but shapes of what?

The elders explained how the features are organized, how they relate to the surrounding landscape, the directions, other sites both near and far, and a bit about what each feature’s functions would have been. They pointed out the meaning behind the features and talked about how these places have current and ongoing power.

Mentz and his crew mapped the entire site during our visit, and related the physical shapes and functions to hundreds of other sites they had recorded. They talked about how many of these types of sites had already been destroyed by development, and how many are endangered. They showed us the life and significance in the rocks, reinforcing the great need to further protect places like this.

While many of the sites being destroyed are on private land, the message was urgent and relates directly to our task of doing a better job within the agency to protect the places held sacred by American Indians and Alaska Natives on national forests and grasslands.

Meeting and working with elders like Looking Horse and Mentz and having them share this kind of information, we are better prepared to bring to this work a good mind and a good heart, and better able to affect the shape of things to come.