It’s not a pleasant memory for Maykia Yang. Fleeing on foot from her native home of Laos at age eight and following her family to Thailand where she spent two years in a refugee camp.

“My father was a soldier and worked for the CIA during the [Vietnam] war. After the CIA pulled out, the Vietnamese took over Laos and we fled on foot for about a month,” said Yang, who now owns a chicken farm in North Carolina.

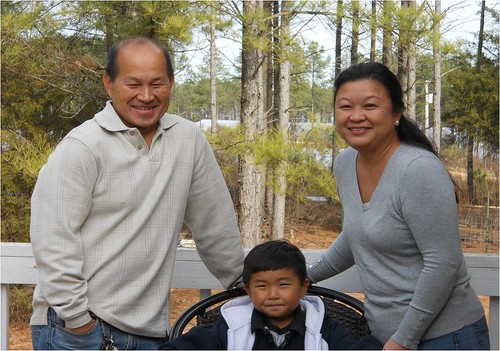

It was the challenges in her path that led her to become an accomplished farmer, but it was her willingness to help others that made her become a voice for minority farmers in her state. Her success prompted Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack to appoint her as a voting county committee member for the Moore County FSA office in North Carolina and she was also selected to serve on the USDA Beginning Farmers and Ranchers advisory committee.

“If I can help others, then they don’t have to go through what I went through,” said Yang.

She takes her cue from an American family that sponsored her family, moving her out of the refugee camp and relocating them to Madison, Wis. She later moved to California and then Phoenix, Ariz., where she put herself through college, received a Master of Project Management degree and met her husband Jim.

Then Yang’s winding path took another more unusual turn.

“When 9/11 occurred, my husband, who was an aviation mechanic, lost his job,” said Yang, who was working in the IT department at American Express during that time. “We were both paying for student loans and we needed to find something where we could stay at home with the kids.”

Yang had siblings living in North Carolina who knew about chicken farms. “We thought, maybe this could be something for us. We could be there and raise a family,” said Yang.

A friend recommended her first stop be the Catawba County Farm Service. FSA provided a guaranteed poultry loan through the NC Finance Authority (NCAFA) for the purchase of the family’s first poultry farm, called Case Farm. Yang’s operation has grown into a 104-acre farm that she operates in partnership with her sister. The family operation is a quality integrator for poultry firm Mountaire Farms, with a total capacity for 286,000 broilers.

“I’ve been trying to bridge the gap,” said Yang. “It took us four years to know that there were programs out there that can help with poultry. Many Hmong farmers don’t know about these programs.”

First starting out, Yang and her husband used a tarp to cover their chicken litter, which cannot be exposed. It remained covered until someone came to haul it away. “We did that for three or four years before we found out there was a program to help,” said Yang.

Today, Yang finds herself trying to educate other Hmong farmers about programs that are available while bringing the issues farmers face to the national level.

“I know one Hmong farmer that has been chicken farming for ten or twelve years and is in a bad financial situation. He doesn’t want to apply for a loan because he feels he is asking the government for help. I try to explain to him that it is there to help,” said Yang. “I understand that there are issues not only in the minority community but in the community itself. I am now in a position to know what the issues are and try to improve them by bringing them to the federal level and seeing what can be done.”