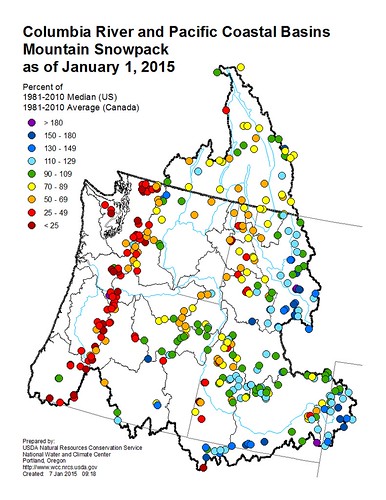

Something about January’s water supply forecast confused me. Current condition maps of the Pacific Northwest are a discouraging spread of red dots, meaning the snowpack contains less than half the normal amount of water. But water supply forecasts for the same region predict normal streamflow in the spring and summer. How can that be? Less snow means less snowmelt, right? Well...maybe.

To rise above my simple, linear thinking, I met with Rashawn Tama with USDA’s National Water and Climate Center. Tama, a hydrologist and forecaster for USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, produces forecasts for the Columbia River basin. His forecasts are built around prediction models that help transform tables of raw data into meaningful maps and colorful dots.

“Keep in mind, the water year starts in October,” Tama said, “What we’ve seen so far in the Pacific Northwest is a lot of precipitation, but most of it has been arriving as rain. Obviously, that doesn’t increase the snowpack, but it’s a key indicator of the water we can expect this summer.”

The prediction models used by Tama and his colleagues take current conditions – snowpack and precipitation – and compare them to the past for the best match. The guiding logic of the prediction model is simple: when these conditions occurred in the past, how much water did we end up with?

It might sound like Tama’s job is automated; like maybe he just presses a button and “Voila!” the forecast is ready. Of course, it’s more complicated than that. Forecasters provide human review for what the mathematical models forecast. Before issuing the forecast, they carefully review those results to make sure they make sense. A large part of their job is to build, refine and review their prediction models, tweaking them to create more accurate forecasts.

For example, in the Pacific Northwest, autumn rains help prime the soil, making runoff more efficient. Water reaches the streams, instead of being absorbed by dry soil. The effect may seem small, but the prediction model accounts for it.

“Persistence is a major factor in our forecasts,” Tama said. “The Pacific Northwest has been in a wet pattern so far, and that could be an indicator of what’s still to come this season.”

Tama is quick to point out that early forecasts can change dramatically as the season progresses.

“If I may use a sports analogy, pretend the water year is like a football season,” Tama said. “And forecasting streamflow is like predicting the Super Bowl champ. Right now we’re still very early in the season. Whether you’re watching football games or monitoring snow storms, the more data you have, the more confident your prediction.”

Most sports analogies are lost on me, but this makes sense. We’ve only seen the first few games of the water season. The team shows early promise; in the past similar teams have performed well. But it’s too early to tell if they’ll go all the way and give us that normal streamflow we’re rooting for. We’ll have to watch and see how the season unfolds.

Tama, along with other forecasters, hydrologists and snow surveyors across the West will keep measuring and giving predictions. Each monthly forecast will be issued with a higher level of confidence.

For the Pacific Northwest, we can hope wet conditions persist and the people of Oregon and Washington will have near-normal streamflow this spring and summer. Keep checking back to find out.

See January’s forecast or see a forecast maps for streamflow or snowpack.