A perfect pie crust is often the measure of a top quality baker. The “blue ribbon” pie crust is light and flaky. Even the best baker’s skills, however, depend on the quality of the ingredients. The quality of flour is based on the quality of the wheat – and measuring the quality of the wheat is a key responsibility of the Federal Grain Inspection Service (FGIS).

FGIS and the Official Service Providers it supervises conduct Falling Number tests as a measure of wheat quality. Scientists and technicians at FGIS’s National Grain Center will soon begin a quality assurance program to monitor these tests and verify the original results to ensure that any procedural issues that could possibly impact the results of these important tests are quickly

addressed. FGIS will monitor a percentage of all tests performed throughout the Official testing system. Last year, over 25,000 Falling Number tests were performed on wheat targeted for sale domestically and abroad.

The Falling Number test is used to determine the pre-harvest quality of wheat. Wheat that begins to germinate or sprout in the field or during storage because of elevated moisture levels can greatly affect the quality of the end product. Sprouting unleashes an enzyme called alpha amylase that breaks down starch in the wheat kernel. The level and quality of the starch in wheat is an important factor in how the end product of wheat functions during the cooking process. Too much sprouting can cause sticky dough, which any baker knows leads to tough pie crusts. It can cause bread, cakes, muffins and other baked products to lose their volume and fall flat. The impact of sprouting is not limited to pies and bread, however, as pasta products with high levels of alpha amylase take longer to cook and produce a cooked pasta product that is too soft – not at all the ‘al dente’ quality preferred by most consumers.

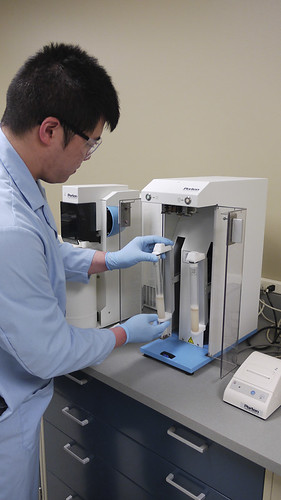

Falling Number is a method used to measure the effect and severity of alpha amylase in wheat before it is milled and used for an end product. An instrument like the one being used in the picture on the left measures the time it takes for a plunger to fall to the bottom of a precision bore glass tube filled with a heated paste of wheat-meal and water. Whole ground wheat or flour and water is added to test tubes and shaken to form a slurry. Stirring rods are inserted into the test tubes, which are then placed in a boiling water bath in the Falling Number apparatus. They are automatically stirred for 60 seconds, which causes the starch-water slurry to thicken. After mixing and heating, the stirrers are released at the top of the slurry. The number of seconds it takes for the plunger to fall to the bottom through the slurry is a measure of the enzyme activity in the wheat – hence the term “Falling Number.” The test requires a specific instrument to run, but can be run virtually anywhere there is good quality water and electricity.

Generally, a Falling Number value of 350 seconds or longer indicates low enzyme activity and very sound wheat. As the amount of enzyme activity increases, the Falling Number decreases. Values below 200 seconds indicate high levels of enzyme activity.

The Falling Number test is recognized around the world as a key measure of wheat quality. Minimum tolerance levels are often required in purchase contracts, especially for wheat targeted for export. FGIS’s Quality Assurance Programs ensure the accuracy of the Falling Number test by standardizing official testing locations across the nation.