The Forest Service manages landscapes, so they are resilient and resistant to threats of all kinds—from fires, to drought, to pest infestations. Forest Service researchers recently confirmed that naturally occurring wildland fire helps create fire-resilient landscapes that limit the start and spread of subsequent fires.

“The extent to which a previous wildland fire helps stop new fires from starting and spreading has not been well studied,” said Sean Parks, a research ecologist with the USDA Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute. Based in Missoula, Montana, Parks has made a career of studying fire regimes in the West to determine how fire naturally responds to climate trends, topography, current weather patterns, fuels and past fires.

Those responsible for managing wildland fires often face extreme pressure to quickly extinguish blazes due to short-term impacts such as smoke pollution or lost timber resources. Parks and his research partners set out to explore the potential benefits of instead managing and monitoring active wildfires before dousing them too quickly.

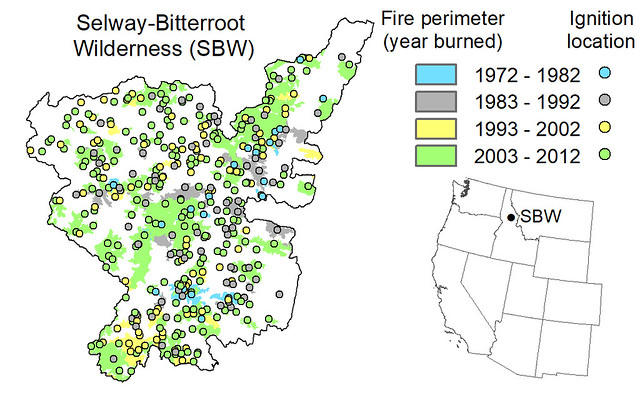

Parks and his partners studied four large wilderness areas in the western United States: three in the northern Rocky Mountains and one in southwestern New Mexico. All four study areas experienced substantial fire activity in recent decades and provided plenty of data to evaluate the relationship between previous fires and the ignition, or start, and spread of later fires.

This “regulatory effect” of natural fire is strongest immediately after it burns but weakens over time. In the warm, dry Southwest, the effect lasted nine years. In the cooler, wetter northern Rocky Mountains, the effect lasted over 20 years. The research results clearly indicate that wildland fire regulated the ignition and spread of later wildfire in all study areas.

The Forest Service will use the information from this study to help make decisions about when and where fires should be suppressed. Allowing fires to burn in more remote areas helps prevent the over-accumulation of dead, woody debris that could fuel larger fires in the future.

Designated wilderness and other protected areas, such as national parks, serve as natural laboratories because many fires are not actively suppressed within them. In addition, little human infrastructure exists to affect a fire’s behavior.

Parks’ research serves as a reminder that wildland fire, under the right fuel and weather conditions, can act as an effective fuel treatment to improve forest health and prevent future blazes from becoming large, costly and more dangerous.

“It’s important to recognize that there are long-term benefits associated with burned landscapes,” Parks said. “There is a growing recognition that our society needs to better co-exist with wildland fire and that it should be restored as a natural ecological process to some landscapes.”