Plunging his shovel into a wheat field covered in soybean residue, Gary Hula hefts up a mound of crumbly soil with a grin. The county is under moderate drought and it’s just above freezing outside, but the soil in his shovel is full of moisture and riddled with worm holes—sure signs of healthy soil.

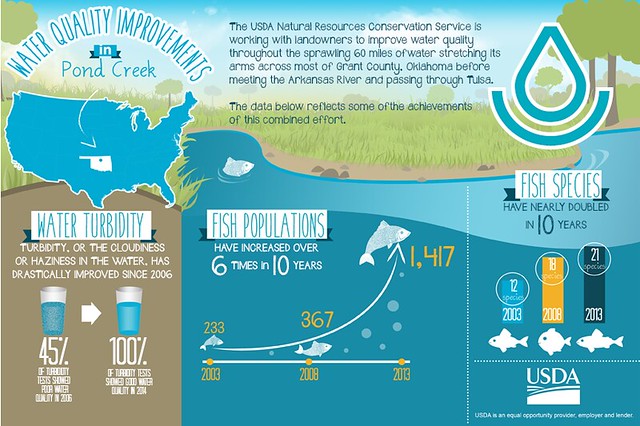

It’s been more than twelve years since Pond Creek was listed as an impaired waterbody, and it’s not just the soils that are unrecognizable. Working with their local NRCS Conservation Planner and the Grant County Conservation District, farmers like Hula—throughout the Pond Creek watershed—are adopting conservation practices that improve water quality. Over 10,000 acres are under nutrient management plans that save farmers money and reduce excess fertilizer getting into streams. Prescribed grazing, grade stabilization structures, range planting and waterway rehabilitation measures have also been adopted on thousands of acres across the county.

Healthier Soil and Cleaner Water

Gary Hula is a wheat, soybean and milo farmer in northern Oklahoma who’s been driving a tractor since before he could drive a car. “When I was growing up, we plowed every acre,” he recalls. “Before we went to no-till, we worked the ground too much. It was so dusty, you couldn’t see to plant a row of wheat,” said Hula. “The soil was like flour, it would just pile up in front of the tractor tires.”

It’s a familiar story in Grant County, where water makes its way to the Mississippi River by way of the Arkansas. It’s also a story that’s been changing since Pond Creek’s water quality issues were discovered.

In 2004, data collected by the Oklahoma Conservation Commission revealed Pond Creek was impaired for elevated turbidity, high concentrations of E. coli and low dissolved oxygen as a result of tilled field runoff and animal waste. By voluntarily implementing conservation practices, farmers and ranchers like Hula are learning that the techniques that make their operations more resilient are the same techniques that revitalize the ecosystems they work in.

Conservation That Works

After four years of planting without a plow, Hula’s soils are unrecognizable—armored by crop residue and full of life. Applying extra nitrogen fertilizer on a single strip at planting allows Hula to more precisely measure fertilizer needs in the growing season, reducing nitrogen runoff. Protecting permanent vegetation along streams on his land means any runoff Hula does produce is filtered on its way to the creek.

Before adopting these conservation practices, Hula watched his neighbors’ success for years. He remembers seeing muddy water roll off his tilled fields while clear water ran off neighboring no-till fields. In the winter, snow accumulated in the residue of no-till fields, hydrating winter wheat, while winds sapped precious moisture from his own tilled fields.

Finally, Hula committed to change: “You’re either part of the problem or part of the solution…I’m not going to turn another clod,” he said.

Four years of no-till and two years of cover crops later, Hula hasn’t looked back. By not disturbing the soil and by keeping living plants in the ground year-round, residue, organic matter and microbes are creating soil structure that stops erosion despite wind and rain and absorbs water and keeps it there longer than tilled soil.

Today, new water quality data shows Pond Creek is clearer, has less bacteria and a booming fish population despite recent drought. Which is why in 2014, Pond Creek was added to Oklahoma’s growing list of delisted streams restored in working agricultural land.

Thousands of acres of no-till, prescribed grazing, cover crops and other high-impact conservation practices have drastically improved the water quality in Pond Creek—benefiting neighbors from Tulsa all the way down to New Orleans.

Top five practices to reduce runoff and erosion in Pond Creek:

- Grass planting

- No-till

- Grade stabilization

- Waterway rehabilitation

- Prescribed grazing

For Gary Hula’s part, he’s eager to continue experimenting with cover crops and reintroducing natural systems on his operation. Unlike many farmers who sell their old plow when they switch to no-till, Hula kept his. It sits rusting next to his new no-till drill.

“My father made his living breaking horses to pull a plow,” he said. “I keep the old disc around to remind me of what I used to do.”