A new study offers the first empirical data proving that female lesser prairie-chickens avoid grasslands when trees are present. The study, highlighted in a Science to Solutions report by the Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative (LPCI), underscores the importance of removing woody invasive plants like redcedar to restore grassland habitat. The new data will help guide USDA’s conservation efforts.

Though sometimes called the “green glacier” for its steady progress across the prairie, redcedar encroachment is far from glacial in speed. Open grasslands can become closed-canopy forest in as little as 40 years, making the land unsuitable to lesser prairie-chickens and other wildlife.

Natural processes like fire once prevented redcedar encroachment, but fire suppression has led to widespread redcedar invasion and loss of grassland habitat.

Researchers from Kansas State University and the U.S. Geological Survey tracked 58 female lesser prairie-chickens for two years on 35,000 acres of privately owned grasslands in southern Kansas using GPS transmitters.

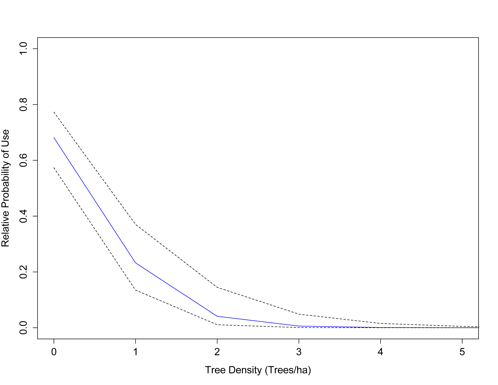

They found that lesser prairie-chickens did not nest in grasslands with more than one tree per acre. Lesser prairie-chickens placed those nests at least 1,000 feet from the nearest tree; and they stopped using grasslands altogether when tree density reached three trees per acre.

The birds require large blocks of structurally-diverse grassland habitat to breed, nest and successfully raise their young. Because of the bird’s landscape-level habitat needs, scientists consider it an indicator species for grassland health. The Great Plains are home to more than 30 other birds that depend on grasslands.

The encroachment of woody plants is a leading threat to the remaining grassland habitat in the southern Great Plains. Removing trees and preventing future encroachment with prescribed fire benefits prairie chicken and other grassland-dependent wildlife. It also leads to healthier rangelands with more forage for livestock.

LPCI, a partnership led by USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), provides technical and financial assistance to help ranchers conserve the bird’s habitat while improving working lands.

Since 2010, NRCS and conservation partners have worked with ranchers to conserve more than 1 million acres of lesser prairie-chicken habitat. LPCI and other NRCS conservation efforts are rooted in science and reports like this one help NRCS fine-tune management strategies. NRCS plans to unveil a new three-year strategy in the coming weeks that will serve as a roadmap for grassland conservation on private lands.

LPCI’s Science to Solutions report is available online. To learn more about technical and financial assistance available through NRCS, visit nrcs.usda.gov/GetStarted or your local USDA service center.