March is National Nutrition Month. Throughout the month, USDA will be highlighting results of our efforts to improve access to safe, healthy food for all Americans and supporting the health of our next generation.

Food insecurity, and the social factors associated with it, can have a profound impact on any U.S. demographic. But two Indian reservations have recently found ways to tackle this very issue and illustrate how a little bit of brainstorming and community-building can go a long way to feed kids and grown-ups.

Ask any parent, and they’ll tell you a good chunk of their income goes toward putting food on the table. While that is taken as a given, what isn’t always obvious are the challenges parents encounter and the behind-the-scenes struggles moms and dads face to make sure there’s enough money to take care of this basic need. School meals are an important part of a child’s daily nutrition. But when the school day is done – and often when children are most hungry – that’s when parents may feel the pinch the most.

Fortunately, the price of nourishing children in the latter hours of the day just got more affordable for residents of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation of the Oglala Sioux Tribe in South Dakota.

In one of the first-of-its-kind initiatives at an Indian reservation, children at Pine Ridge will have access to supper at Pine Ridge School thanks to the USDA’s Child and Adult Care Food Program. CACFP will provide federally-funded meals on the reservation through the At-Risk Afterschool Meals component of the program. The project is a partnership between Oglala Lakota College, Pine Ridge School, the South Dakota Department of Education, and USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service. Oglala Lakota College serves as the actual sponsor for the program.

“I am honored that we, as the college, were involved in this endeavor and that we were able to sponsor such an important collaboration with USDA, State of South Dakota, and Pine Ridge School,” said Janice Richards, Director of Oglala Lakota Head Start and Early Head Start Program.

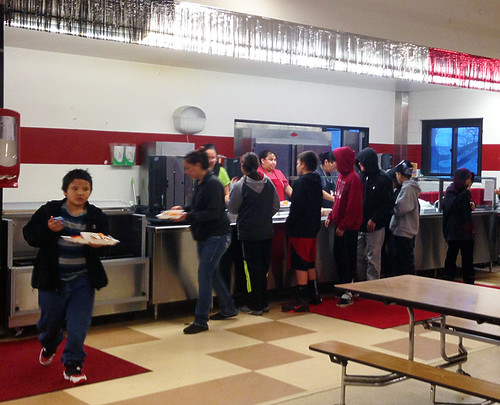

Currently, about 100 to 150 students receive meals nightly at the Pine Ridge School dormitory. Back in January, CACFP began providing reimbursement for these meals, making it possible to expand the outreach to area children. The program is expected to grow gradually and potentially serve up to 300 to 350 children.

But Pine Ridge isn’t the only place where great things are happening in tribal nations around the country. Residents of the Spirit Lake Sioux Tribe in North Dakota are also eating healthier, and now have fresher and more varied food choices as part of a change to their Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservation (FDPIR).

In the last four years at Spirit Lake, FDPIR had seen a 93 percent increase in participation due to policy changes that simplified and improved administration to expand access to the program. To keep up with the demand and sensing it was time for the program to evolve for a more appealing experience, regional FDPIR staffers made sweeping changes. They secured funding to accommodate the big changes coming, and then moved to a new warehouse they knew could accommodate their plans. Now, consumers can pick up their food at a warehouse that’s been redesigned to mimic a more traditional grocery store shopping experience. Several tribes in other U.S. regions have this model, but this is a first for the Mountain Plains Region.

“It was a challenge to move, and there has been a learning curve for everyone,” said Mary Greene-Trottier, director of the FDPIR program, “but there have been so many positive effects from this and the clients are very happy.”

Trottier said the new system also allows residents to come back for food more than once a month, improving their access to fresher produce and that they can see, touch and feel food before they select it.

The current warehouse is also home to the Benson County Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) office. While participants in FDPIR cannot simultaneously receive SNAP benefits, Trotter sees opportunities to partner in offering nutrition education to beneficiaries of both FNS programs.

These programs are excellent examples of how communities can still come together, share their local culture, and collaborate on ideas that will ultimately bring about healthier future generations.