The Natural Resources Conservation Service works with ranchers and partners to improve habitat for sage grouse with funding through the Sage Grouse Initiative. Focusing on privately-owned lands, the initiative covers the 11 Western state range of the bird. About 40 percent of the sage grouse dwell on private lands. David Naugle is a wildlife professor at the University of Montana and the science advisor for SGI, an NRCS-led partnership. —Tim Griffiths, NRCS

By David Naugle, Science Advisor, Sage Grouse Initiative

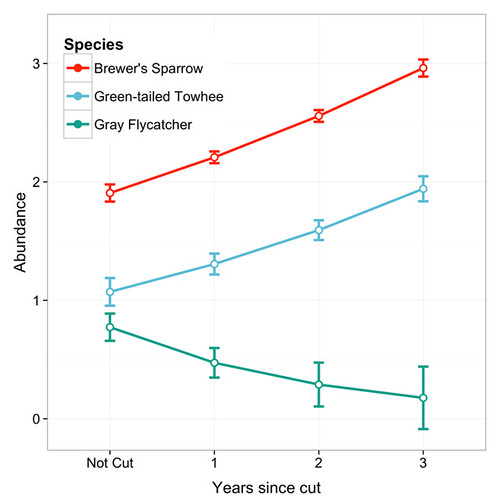

Restoring sagebrush ecosystems not only benefits ranching and sage grouse but other wildlife, too. New data show that populations of Brewer’s sparrow and green-tailed towhee, two sagebrush-dependent songbirds, climbed significantly in places where invading conifer trees were removed.

Three years after removing trees, Brewer’s sparrow numbers increased by 55 percent and green-tailed towhee numbers by 81 percent relative to areas not restored, according to a new report released by the Sage Grouse Initiative (SGI). These two songbirds, both identified as species of conservation concern by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), serve as early indicators of the effectiveness of restoration work.

Aaron Holmes, Director of Northwest Wildlife Science and a Research Associate with Point Blue Conservation Science, led the research, assessing the biological outcome of songbirds after habitat restoration in the Warner Mountains near Adel, Oregon. Population increases each year after trees were removed suggest that growth in the populations of these two species may increase even more with time as more displaced birds increase their use of restored habitat.

“The number of these songbirds using the restored shrublands was more than double that of adjacent areas that had not yet been cut, telling us that Brewer’s sparrow and green-tailed towhee preferred the open shrublands created through conifer removal,” Holmes said.

Conifers invade and degrade sagebrush ecosystems, dispersing the wildlife that once called the habitat home. Over the past two centuries, fire suppression, historic overgrazing and favorable climate conditions have led to spread of conifers into sagebrush habitat. More than 350 species of wildlife depend on the sagebrush ecosystem, and many of those species have suffered population declines because of these invading trees and other threats.

While the numbers of Brewer’s sparrow, green-tailed towhee and other songbirds climbed, Holmes’ research showed a dip in gray flycatcher numbers. That outcome was expected as the gray flycatcher prefers a mix of conifer and sagebrush habitats. The gray flycatcher population in Oregon has tripled since monitoring began in the mid-1960s. In contrast, Brewer’s sparrow have declined approximately 60 percent and green-tailed towhee by 64 percent.

Roughly 80 percent of invading conifers in sagebrush habitat are in early phases of woodland succession. SGI, a partnership led by USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), removes invading conifers in places where trees are younger and sagebrush is still dominant. Since 2010, ranchers have restored 400,000 acres of otherwise suitable habitat. Nearly half of cuts are in Oregon, where conifer removal through the SGI has increased by 14-fold. Threat alleviation on private lands in Oregon is two-thirds complete inside of priority areas.

Ongoing conifer removal is part of a larger four-year strategy, called Sage Grouse Initiative 2.0, which NRCS unveiled last month. Under 2.0, an additional 246,000 additional acres will be cut by 2018. In Oregon, where Holmes conducted research, the conifer threat on private lands will be removed in all sage grouse priority areas. The strategy also works to reduce wildfire and fence collisions, remove invasive grasses and protect key habitats. By 2018, the strategy will raise the footprint of restored sagebrush habitat to approximately 8 million acres – an area more than seven times the size of the Great Salt Lake.

Songbirds are not the only sagebrush wildlife to benefit from sage grouse conservation. In a companion study on mule deer, scientists in Wyoming found that conservation measures implemented to benefit sage grouse also doubled the protection of mule deer migratory corridors and winter range.

Now in its sixth year, SGI has matured into a primary catalyst for sagebrush conservation across the West. SGI’s shared vision of wildlife conservation through sustainable ranching provides win-win solutions for producers, sage grouse and hundreds of other sagebrush species. The FWS is expected to make a listing decision later this month.

Learn more about NRCS’ sage grouse conservation efforts. For more on technical and financial assistance available through conservation programs, visit nrcs.usda.gov/GetStarted or a local USDA service center.