Sometimes Mother Nature and hard work come together to produce a bountiful harvest on the farm. But what if the grocery store, distributor, or processor that the farmer sells to can’t handle any excess? Or, what if a percentage of the crop turns out too big, too small, or oddly shaped and no one will buy it? Organizations across the country are working with farmers to get this wholesome produce to people who need it.

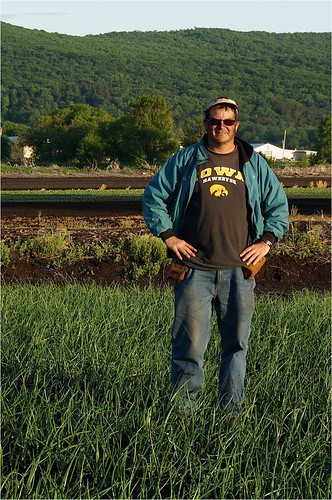

Many farms may want to donate directly to a food bank, but are discouraged because they currently can’t claim a tax deduction for the donations. To help farms offset the costs of the labor required to harvest the crop and the packaging to transport it, many food banks and food recovery groups are able to assist the farmer with the “pick and pack out” (PPO) cost. The PPO cost can be very beneficial to a farmer. Chris Pawelski, a fourth generation onion farmer at Pawelski farms in Goshen, New York, donates his nutritious-but-undersized onions to City Harvest. City Harvest is a food rescue organization in New York City that has been connecting good, surplus food with hungry New Yorkers since 1982. The PPO cost that is paid to Pawelski by City Harvest in some years was the determining factor in keeping his farm from losing money.

In 2011, Hurricane Irene and Tropic Storm Lee destroyed Pawelski’s onion plants, leaving 3 out of 51 acres harvestable and Pawelski was left several hundred thousand dollars in debt. His dire circumstances led Chris to famously auction a 50 lb. bag of onions for $150,000 online. The following 2 years, hot and dry weather left many of his onions undersized for the No.1 grade required by many supermarkets. Pawelski could have sold them to a secondary processor to turn into onion flavoring for processed food, but they had the same nutritional value as standard sized onions so he preferred that they help feed low-income families. He donated them to City Harvest, and in this case, the PPO cost provided was the same amount as what a processor would pay.

“City Harvest has been a fantastic organization to work with over the years. Not only have they helped people who they provide food for, but they have immensely helped farmers like me. If not for City Harvest, in 2012 and 2013 I would have not made a living and provided for my family, and I would have actually needed food assistance,” says Pawelski. City Harvest works with 77 farms across the country including in California, Maine, and Florida.

Pawelski would like to see food banks and food rescue organizations across the country receive grants to purchase secondary grade produce from farmers at market price. “Some sort of ‘Farm to Food Bank’ grant would help out millions of food insecure people, giving them access to healthy and nutritious food. It would greatly benefit the wholesale farmer, opening up a massive market for produce that up to this point has been inaccessible,” explains Pawelski.

For food waste advocates, Pawelski’s proposal would also have the added benefit of keeping food from rotting out in the fields or being plowed under after all the hard work and resources that went into growing it. Advocates believe helping farmers create new markets for their secondary produce could help farmers, feed low-income people quality food, and keep food out of landfills, creating a win-win-win situation.