This post is part of the Science Tuesday feature series on the USDA blog. Check back each week as we showcase stories and news from the USDA’s rich science and research portfolio.

You’ve probably heard that the honey bees in this country are in trouble, with about one-third of our managed colonies dying off every winter. Later this week, we will learn how the honey bees survived this winter. With severe weather in a number of areas in the U.S. this winter, a number of us concerned about bees will be closely watching the results.

While scientists continue work to identify all the factors that have lead to honey bee losses, it is clear that there are biological and environmental stresses that have created a complex challenge that will take a complex, multi-faceted approach to solve. Parasites, diseases, pesticides, narrow genetic diversity in honey bee colonies, and less access to diverse forage all play a role in colony declines. To confront this diverse mix of challenges, we require a mix of solutions – the odds are that we won’t find one magic fix to help our honey bees.

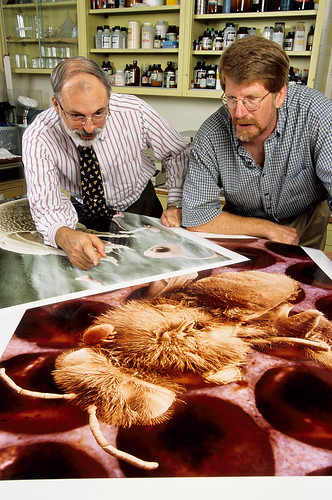

The parasitic mite Varroa destructor remains the major factor in overwintering colony declines. The varroa mite’s full name is Varroa destructor, and it is perhaps the most aptly named parasite ever to enter this country. An Asian native that arrived here in 1987, Varroa destructor is a modern honey bee plague. The problem is that varroa mites are becoming resistant to the miticides used to control them. And while there are folk remedies and organic treatments, none of those work as well. New treatments are in the pipeline, but another miticide can only be a short-term solution as the cycle of new treatment and new resistance continues.

USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) is looking to the genetics of both the mite and the honey bee for long-term solutions. ARS has put together a program to breed bees that can naturally resist varroa mites. For example, some bees have a propensity for nest cleaning and grooming behaviors, including aggressively kicking varroa-infested pupae out of the hive. The idea is to breed bees specifically to intensify such traits. ARS is also working on improving nation-wide epidemiological monitoring, finding genetic and/or biochemical disruptors and a host of other possibilities to help beekeepers and honey bees fight off varroa.

More important work like this ARS research could be supported by USDA in the future. As part of the current budget, USDA has requested $25 million to establish the Pollinator and Pollinator Health (PPH) Innovation Institute. The PPH would be administered by the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) and, with help from stakeholders, would be responsible for addressing the biological, environmental and management issues associated with the wide-spread decline of honey bees and other pollinators in our country. If established, the PPH will support the activities already identified in the joint USDA-Environmental Protection Agency action plan and build on current pollinator research and extension projects.

USDA’s dedicated scientists and researchers are working to help the honey bees. There are other pollinators, and some crops like corn, wheat, rice and even soybeans are mostly wind-pollinated, but the 90 or so crops that managed honey bees pollinate for farmers—berries, nuts, fruits and vegetables—are what add color, taste and texture to our diet. So USDA scientists are working to find a solution to varroa mites and other problems associated with honey bee health, so you continue to enjoy the bounty of US agriculture.