It has been 88 years since the hammers and crowbars went silent. Sweat ran for more than a month as teams of workers smashed and destroyed Los Angeles’s original buildings between First, Temple, Spring and Main streets.

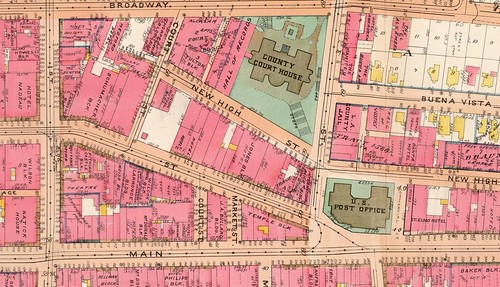

Construction began in the 1850s, and these buildings quickly became known as the cradle for an infant city. The footprint is now buried deep below present day Los Angeles City Hall and its adjacent park. It was not until March 2014 that local historians were reminded of this past for the second largest city in the United States.

It started last fall when a soil survey team from the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) began to dig a soil pit in City Hall Park adjacent to city hall, as part of the agency’s soil survey.

NRCS soil surveys provide soil information, data, and maps to a wide range of users across the nation. Traditionally, soil surveys assist agricultural users make optimal decisions regarding crops, irrigation, erosion control, wildlife habitat, water conservation and more.

But today, more and more people in urban areas, like Los Angeles, are realizing the importance of understanding and protecting soil. Los Angeles city managers intend to use the completed survey data for their future planning and development.

While collecting soil samples, NRCS scientists unearthed the first three feet of material, nothing out of the ordinary struck them from a typical soil dig in an urban center. But they dug a little deeper and discovered something extraordinary.

“At first glance, I thought we had unearthed crushed up brick material, which is common of anthropogenic soils in urban areas,” said Randy Riddle, NRCS soil survey project leader. “After digging a slightly larger hole to get a better view, we noticed that whole red bricks were leveled horizontally. The oriented brick layer was continuous throughout the bottom of the excavated area.”

The discovery led to consulting with a number of local historians to identify what the group found. At first thought, it seemed like the red bricks made up an old brick road now buried deep.

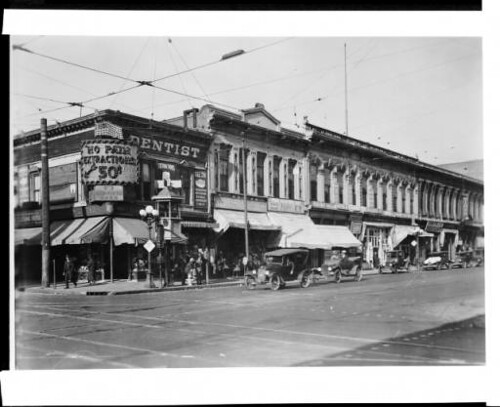

But after multiple discussions with historians and looking at dated pictures of the exact spot, it turns out the bricks constituted a subfloor for a former dentist’s office that boasted painless teeth extractions for a mere 50 cents.

The dentist’s office was one of the final tenants in the Lichtenberger Building, located on the corner of First and Main streets, and destroyed in 1926 to make way for the city hall complex.

In a photograph provided by the University of Southern California Libraries Special Collections staff, it is easy to determine where the soil pit was in relation to which business occupied that space years ago.

“The big block that City Hall now sits on, including the park, was formerly chockablock with groceries, haberdasheries, etc.,” said Brent Dickerson, historian and author of books about Los Angeles history and other subjects. “The buildings were usually raised above ground level, so that water from the street wouldn’t flow in, and the sub-structural floor wouldn’t need to be very deep to be below the ground floor.”

This determination was amplified further when discussing the find with a representative for Los Angeles’s Project Restore. “Red brick would have been for the foundations, red pavers would have been floors or walkways, and black would have been alleys or streets,” said Kevin Jew, chief operating officer for Project Restore.

Project Restore is a Los Angeles organization dedicated to the restoration and maintenance of valuable city buildings, preserving these landmarks in order to maintain the culture and history that reside within them.

Construction of Los Angeles City Hall required more than just demolishing many of the city’s first buildings. First, Temple, Spring and Main streets actually formed a triangle until 1926 and were reshaped into a rectangular configuration. It took two years to construct City Hall, and it remained the tallest building in Los Angeles until 1964.

“The Temple Block anchored a bustling commercial area until the mid-1920s,” said Nathan Masters, who has written extensively on Los Angeles history on behalf of the USC Libraries. “Then, construction of L.A.’s new Civic Center erased entire city blocks of old brick buildings and other historic structures from the map. The Temple Block crumbled, Spring Street straightened itself out to become parallel with Main, and the city’s old commercial heart beat no more.”

The soil survey for the southeastern section of Los Angeles County, which includes downtown Los Angeles, has been a recent endeavor for NRCS’ soil scientists. The rest of Los Angeles County was mapped over the past 60 years but downtown Los Angeles remained elusive until now.

With the proper permissions from city officials, Riddle has a long road ahead to complete his urban soil mapping for this massive city. It will be interesting to see what other treasures Riddle unearths down the road.